Exploitation in the cocoa industry

Vegan Society of Canada

Published January 14th 2022

Updated April 2nd 2025

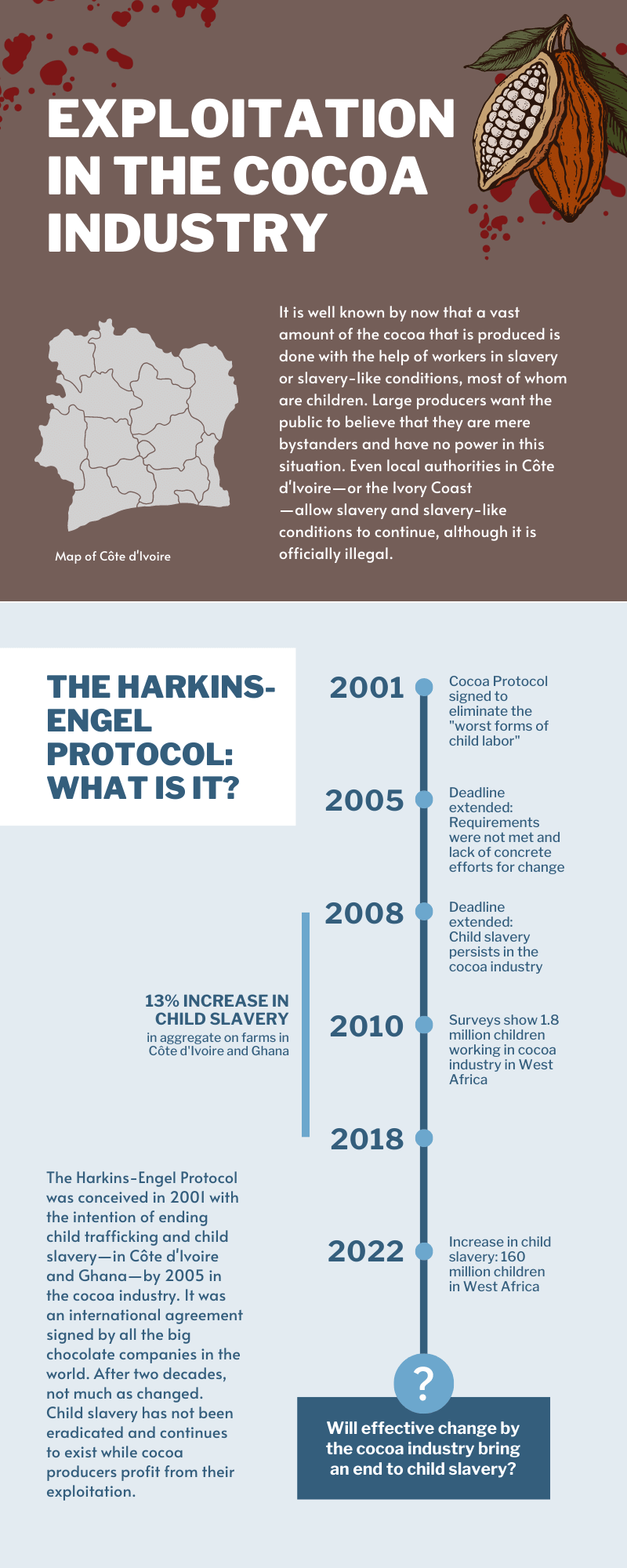

September 2021 was the 20th anniversary of the failure of The Harkin-Engel Protocol. Twenty years later, most chocolate remains unsuitable for vegans and we will ban from vegan certification Nestlé’s, Cadbury, Hershey and Lindt’s plant-based chocolate bars including but not limited to Nestlé’s plant-based KitKat, Cadbury’s Plant Bar, and Hershey's Oat made chocolate.

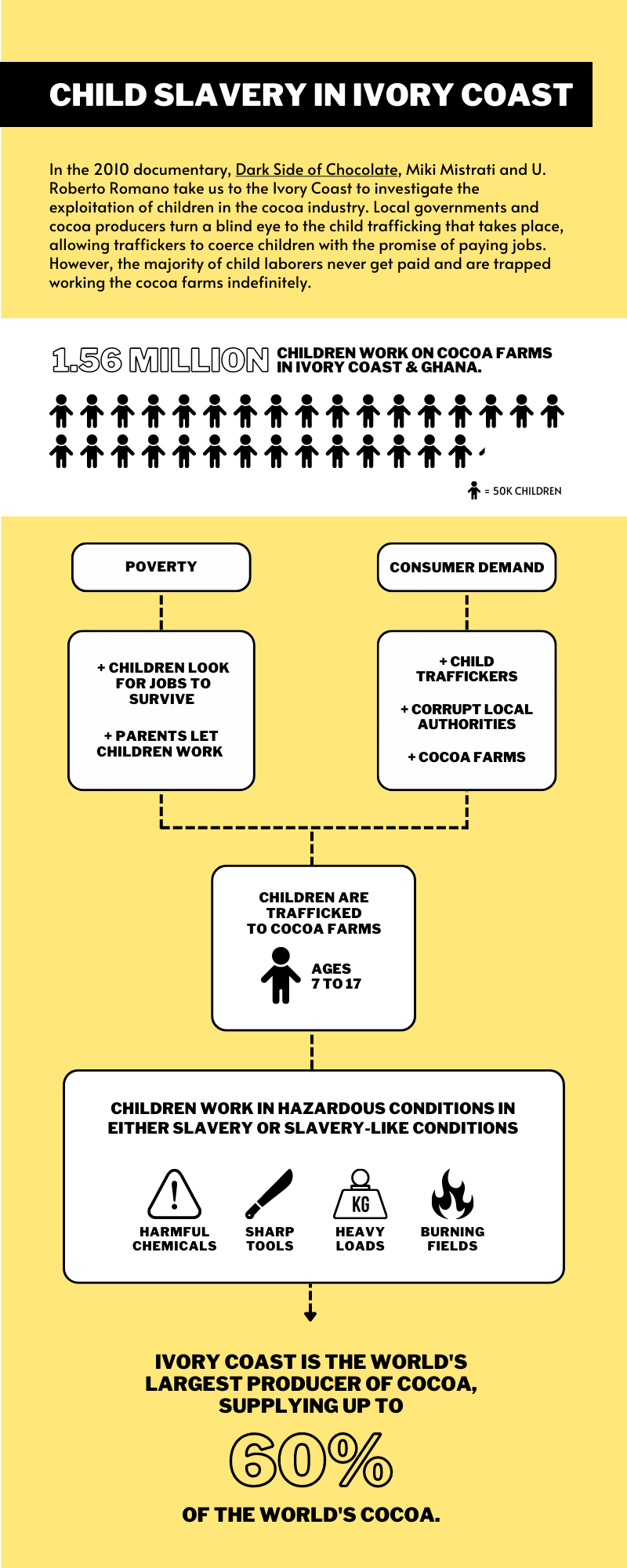

It is well known by now that a vast amount of the cocoa that is produced is done with the help of workers in slavery or slavery-like conditions. More recently, a report and a lawsuit against major chocolate producers once again highlighted the exploitation of animals in the production of cocoa. Large producers want the public to believe that they are mere bystanders and have no power in this situation:

Twenty years after they acted collectively and signed the Harkin-Engel Protocol in 2001 and promised to end their admitted use of the “worst forms of child labor,” they argue to a U.S. federal judge that they are mere purchasers of cocoa, they don’t have sufficient knowledge of forced child labor to be liable, they have no control over the cocoa farmers in Cote D’Ivoire, because they are so far removed from cocoa harvesting operations, holding them liable for using cocoa harvested by enslaved children would be akin to holding consumers of chocolate liable, and, by the way, they “strongly condemn the use of forced labor.”

The report which only covers the worst forms of child labour, and not all slavery and slavery-like conditions like forced labour or human trafficking, paints a grim picture. For-profit corporations that produce chocolate had agreed since 2001 to eliminate the worst forms of child labour. Would it surprise anyone what happened next? Not only did chocolate producers not respect the agreement, but the rate of the worst forms of child labour also increased:

The prevalence rate of hazardous child labor in cocoa production in agricultural households in cocoa growing areas of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana increased by 13 percentage points in aggregate between 2008/09 and 2018/19 (from 30 percent in 2008/09 to 43 percent in 2018/19).

In an effort to confuse the public, the report talks about something we refer to as exploitation intensity, which is similar to emission intensity for climate change, whereas if you produce 1 kg of chocolate with 10 slaves your exploitation intensity is higher than if you produce 2 kg of chocolate with 15 slaves. The report claims that while the absolute amount of exploitation has increased over time, their intensity is less as the industry produces more chocolate with fewer slaves and people in slavery-like conditions.

One might wonder what are these worst forms of child labour that chocolate producers had agreed to eliminate in the Harkin-Engel Protocol; could it be that they simply set their sights too high? These are defined in the International Labour Organization C182:

(a) all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale and trafficking of children, debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory labour, including forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict;

(b) the use, procuring or offering of a child for prostitution, for the production of pornography or for pornographic performances;

(c) the use, procuring or offering of a child for illicit activities, in particular for the production and trafficking of drugs as defined in the relevant international treaties;

(d) work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.

We would argue that their sights are set way too low because there is still a lot of animal exploitation that does not reach the official definition of slavery or slavery-like conditions. After having failed to achieve all the elements of the agreement by the July 2005 deadline, it was extended to 2008, then 2010, 2015 and finally 2020. The creator of the award-winning documentary The Dark Side of Chocolate said in a 2012 interview when ask about the never-ending extension of the deadline:

I think if we talk again five years from now, we will be discussing the same issues. I know there is a lot of pressure on the industry right now so I think we will soon see some changes — only I doubt it will be through the Harkin-Engel Protocol. I think it will be through consumers who demand change and better conditions for the workers.

In hindsight, he was completely right. Nothing was done then and nothing has been done since then, and we agree that it is through consumers that the industry will change.

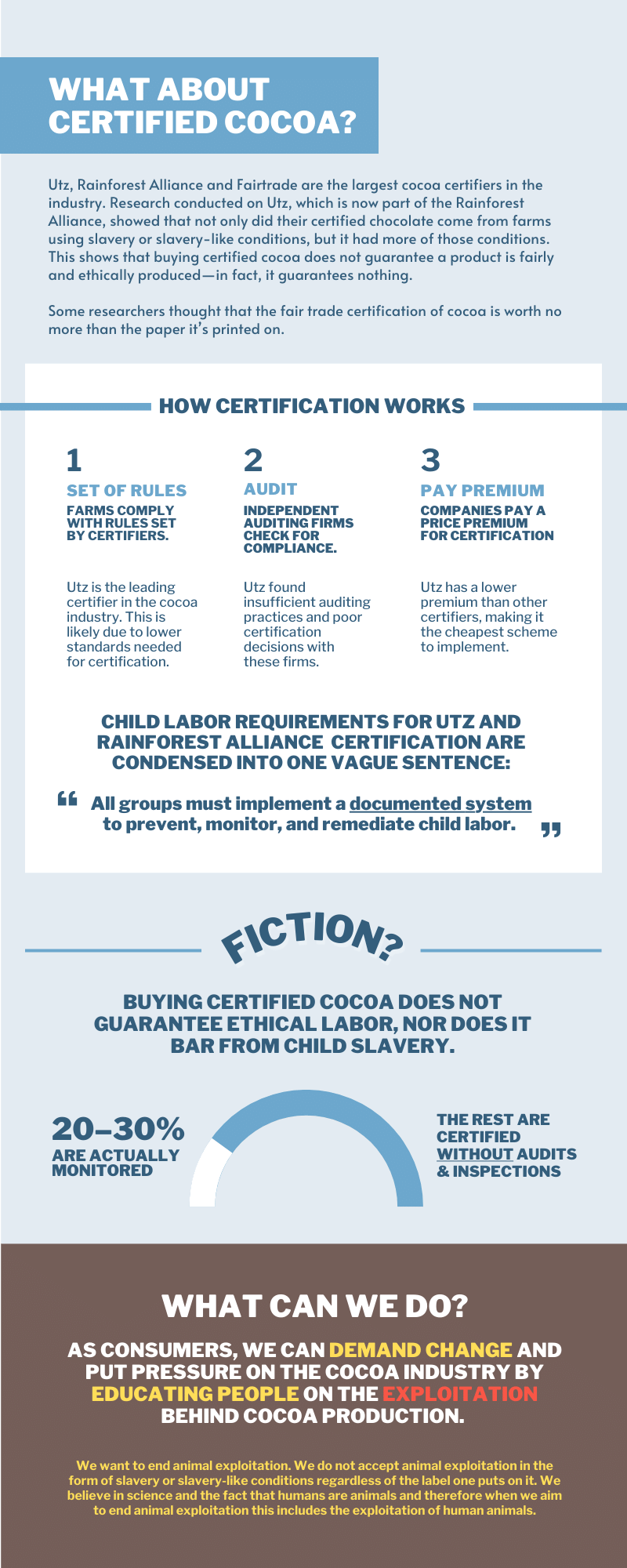

Now let’s address what some of you might be thinking: Is the plant-based KitKat not sourcing 100% cocoa from the Nestlé Cocoa Plan in conjunction with the Rainforest Alliance? The answer is yes, but just like the huge problem with vegan certification, there are serious problems with the fair trade certification. One paragraph of the lawsuit against the chocolate producer sums up the situation best:

Further, groups like “Fair Trade” and Rainforest Alliance (which absorbed UTZ, the third labeling initiative) participate in this fraud by labeling all of their company partners’ cocoa as meeting their standards when they know that only 20 to 30 percent at most is even being partially monitored. Additionally, these so-called “fair trade” initiatives mislead the public by creating the false impression that they are certifying cocoa as child-labor-free when they do not in fact assess the extent of child labor in their member companies’ production.

Furthermore, as highlighted, it is important to note the clever use of words that none of those certifications are claiming it is free of slavery or slavery-like conditions, simply that it is “fair trade” or “sustainably sourced.” These words have no more legal meaning than the word “natural” does. An article in 2019 by the Washington Post gives a good overview of the various issues in fair trade certification. Research conducted on UTZ, which is now part of the Rainforest Alliance, showed that not only did their certified chocolate come from farms using slavery or slavery-like conditions, but it had more of those conditions. That is correct, certified cocoa had more slavery and slavery-like conditions than non-certified cocoa. Some of the researchers thought that the fair trade certification of cocoa is currently worth no more than the paper it’s printed on:

Consumers believe that by buying certified cocoa they are doing something good for the environment, or children, or farmers, but that is a fiction.

Certification misleads consumers to believe that farmers earn a living wage, their children go to school, and labor conditions are decent. From the perspective of a farmer living in abject poverty, this is morally outrageous.

We have previously discussed at length all the issues in vegan certification, and many of these issues are present in the fair trade certification of cocoa as well. The reason UTZ has become the main certifier of cocoa is likely that its standard is the least stringent and therefore the cheapest to implement. Their fair trade premium was the lowest, sometimes half as much as others. As we have said, corporations are forced to maximize profits over anything else and they will naturally gravitate toward the least stringent certification scheme, which usually translates into lower costs of implementation. This doesn’t include corporations that exploit label fatigue and start their own certification scheme like Nestlé’s Cocoa Plan or Mondelez’s Cocoa Life.

Infographics

Our vision is clear: We want to end animal exploitation. We do not accept animal exploitation in the form of slavery or slavery-like conditions regardless of the label one puts on it. It is irrelevant whether animals walk on two or four legs, or whether large producers are innocent bystanders or not. We will never certify vegan a product when there is reasonable suspicion it is the result of slavery or slavery-like conditions. It is unconscionable and a direct violation of our vision and mission along with destroying the ethical foundation on which the vegan philosophy can solidly rest.

We always encourage people to support organizations that align with their beliefs. Ours are clear: We believe in science and the fact that humans are animals and therefore when we aim to end animal exploitation this includes the exploitation of human animals. Our vision is not to move exploitation from four-legged animals to two-legged animals, but to end it. It is outrageous that any goods be produced with slavery or slavery-like conditions, since it is already made illegal by various treaties that most countries are signatory to, but it is ineffable that these goods be certified vegan.

It is for this purpose that we ban from vegan certification Nestlé’s, Cadbury, Hershey, and Lindt's plant-based chocolate, and deem them unsuitable for vegans. Furthermore, most chocolate products available in the marketplace today derive from animal exploitation and are also unsuitable for vegans.

Disclaimer

This article was contributed by our member Vegan Society of Canada. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of Vegan World Alliance.